The Art of Influence and Motivation

Introduction:

One of my favorite definitions of leadership comes from Dwight D. Eisenhower, who said, “Leadership is the art of getting someone else to do something you want done because he wants to do it.” Leadership is a science and an art. The science of leadership is based on behavioral research, theories, and practices that focus on how people are wired, influenced, and motivated. The art of leadership focuses on how leaders apply science to create an environment in which people are happy coming to work, engaged, and driven to internalize the goals of the organization and meet or exceed the organization’s goals. The ability to inspire and guide individuals towards a common goal is a hallmark of great leadership. To better understand this complex interplay, we will delve into several key concepts: social exchange theory, the locus of leadership, power bases, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, followership, and idiosyncrasy credits. We will explore each of these elements to shed light on how leaders can harness the power of influence and motivation for success.

Social Exchange Theory: The Foundation of Influence

At the heart of understanding how people are influenced lies the social exchange theory. Relationships are built or ended based on a cost-benefit analysis. Think about it, when you meet someone, you determine rather quickly if you want to pursue or build a relationship with that person. In fact, research indicates that in as little as 1/10 of a second, you will make judgments concerning a person’s likeability and trustworthiness. This initial impression jump-starts the psychological contract process between you and the person. If you determine the relationship is beneficial, you will pursue building that relationship. If not, you will end the relationship and part ways.

This relationship-building process is no different in an organizational setting. Social exchange theory posits that leader-follower relationships are built on the principle of reciprocity, where individuals seek to maximize rewards and minimize costs. In this context, the leader induces the follower to contribute labor, skills, and knowledge in return for pay, promotions, recognition, belongingness, and a positive leader-member relationship. Effective leaders understand the importance of striking a balance between what they provide and what they expect in return.

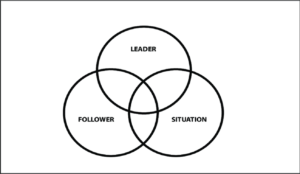

Social exchange theory is made up of three elements: the leader, the follower, and the situation. Leadership takes place where the leader, the follower, and the situation intersect. This intersection is the leadership moment, also referred to as the locus of leadership. In the following, I will elaborate on each of these areas.

- The Leader: This element is based on the leader’s view of others, and how the leader’s view affects the leader’s use of power bases to influence and create motivation in followers.

- Theory X/Theory Y: The leader’s view or assumption of others impacts which power bases the leader will use to influence followers. McGregor’s research led to the development of theory X and theory Y assumptions about followers. According to McGregor, a theory X leader’s assumption of followers is that they are lazy, lack ambition, do not want responsibility, and prefer to be told what to do (i.e. be led). In contrast, a theory Y leader’s assumption is that followers want to make a difference at work, take initiative, take on and accept responsibility, and want to make decisions.

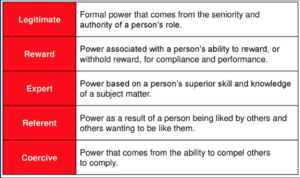

- Power Bases: The ability to understand and use influence to create motivation in others is a fundamental skill that sets successful leaders apart. Influence is the ability to persuade or affect someone’s behavior or decisions. Effective leaders have a clear understanding of the different sources of influence that drive human behavior and they know how to use them to create motivation. French and Raven’s Power Base Taxonomy presents an invaluable framework that allows us to dissect the sources of power leaders use to influence others. Each power base, listed below, has a different way of influencing, others.

- Legitimate Power: This power base can influence others based on the supervisor’s authority. For example, a supervisor can give orders and the employee has the responsibility to follow the orders given based on the supervisor’s authority.

- Reward Power: This power base can influence others by offering incentives for achieving goals and recognizing hard work. The key to reward power is the person who is offered the reward must value it. If not, the reward may not create motivation in the person to complete the task.

- Coercive Power: This power base can influence others by creating fear of negative consequences (or discipline) for not meeting expectations or following through with the order(s) given.

- Expert Power: This power base can influence others by providing guidance and mentorship based on knowledge and expertise.

- Referent Power: This power base can influence others by setting an example of behavior and inspiring others to follow their lead. Think about a great coach or great boss/leader you have had. You will walk through fire for those that hold referent power with you.

What I have found in my research and experience is theory X leaders tend to rely on the use of legitimate and coercive power bases to influence others, while theory Y leaders tend to use referent and expert power bases.

- The Follower: This element is based on how the follower views the relationship with the leader, the type of power base the leader uses to influence the follower, the follower’s needs, and the follower’s followership style.

- Relationship/Power Base Usage: Take a couple of moments to recall times you completed a task based on the relationship you had with your supervisor or the influence the supervisor used. Think of a time when your supervisor asked you to do something, and you did it because you liked or admired that person. Think of a time when your supervisor asked you to do something, and you did it because the supervisor offered you something you valued in return for completing the task. Think of a time when your supervisor asked you to do something, and you did it because the supervisor had the authority over you to demand you do what the supervisor asked. Think of a time when your supervisor asked you to do something, and you did it because the supervisor was an expert in the thing the supervisor asked you to do. Think of a time when your supervisor asked you to do something, and you did it because you were afraid something negative would happen to you if you didn’t.

How the follower views the leader or the type of power base (influence) the leader uses impacts the follower’s motivation to complete the task.

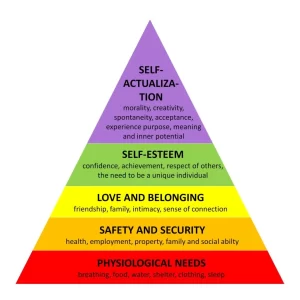

- The Follower’s Needs: A follower’s needs impact the follower’s motivation and how the follower is influenced. To this end, Abraham Maslowdeveloped a hierarchy of needs theory that proposes people are motivated based on needs. Maslow’s hierarchy includes the following five needs:

- Physiological: These are basic needs such as food and water. A person’s job and salary would most likely address this need.

- Safety: The fulfillment of this need includes a safe environment, free from threats and violence. Job security at one’s work most likely will address this need.

- Belongingness: The fulfillment of this need includes being accepted, building friendships, and becoming part of a group or team. At work, this need is attained by building good relationships with coworkers and supervisors, and participation on a group or team.

- Esteem: This need relates to a positive self-image. This need is fulfilled when a person attains responsibility, status, and/or recognition at work.

- Self-actualization: This need represents the quest for self-fulfillment. At work, this need is fulfilled when one is given opportunities to learn, grow, and advance within the organization.

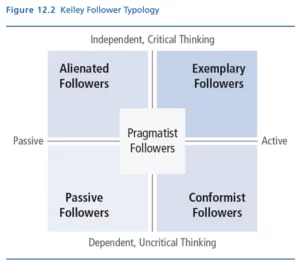

- The Follower’s Followership Style: Robert Kelley identified five distinct followership styles (alienated, conformist, passive, pragmatic, and exemplar) that individuals fall into based on their adult development phase, needs, behavior, and the relationship they have with the leader.

The alienated follower is characterized by a negative attitude towards the leader and the organization. The alienated follower is critical and resistant to change and may feel powerless or unsupported. While the alienated follower may have valuable insights and perspectives, the alienated follower’s negative attitude can make him or her challenging to work with and may hinder organizational success.

The conformist follower is characterized by a strong desire to fit in and follow the rules. The conformist follower is known as a “yes person.” While the conformist follower is reliable and dependable, the lack of independent thinking can limit the conformist follower’s potential to contribute new ideas and perspectives to the organization.

The passive follower is characterized by a lack of engagement, critical thinking, and initiative. The passive follower may be indifferent to the leader and the organization and may simply go through the motions without taking ownership or responsibility. The passive follower fails to make meaningful contributions to the organization’s success.

The pragmatic follower is known as a survivor. The pragmatic follower is a chameleon, who often moves between the other followership styles, depending on the leader or the mood of the organization.

The exemplary follower is characterized by a strong commitment to the leader and the organization. The exemplary follower is a critical, independent thinker, who is also proactive, dependable, and willing to accept responsibility. The exemplary follower is creative and innovative and actively seeks out opportunities to contribute to the organization’s success. The exemplary follower is committed to supporting the organization’s vision and goal and is willing to tactfully and respectfully speak up when he or she disagrees with the leader.

- The Situation: This element is based on the leader-follower relationship and idiosyncrasy credit theory. The situation occurs in the leadership moment when the leader decides on a course of action. The followers will view the leaders’ actions/decisions based on the group’s norms, the group’s expectations, and the impact the decision has (positively or negatively) on the group.

Idiosyncrasy credits are the currency of trust in leadership. They represent the balance of trust a leader has with their followers and can be spent or saved depending on the leader’s actions and decisions. Leaders build idiosyncrasy credits with their followers by consistently meeting their followers’ expectations, making what are considered good and fair decisions, and demonstrating integrity. Leaders lose idiosyncrasy credits if they make poor decisions, treat followers poorly, demonstrate a lack of competence, or go against the group’s norms.

Putting it all Together: The Effective Leader’s Approach

Leaders succeed or fail based on how they view and interact with their followers, the types of power bases they rely on to influence, their willingness to understand and meet their followers’ needs, and their ability to build idiosyncrasy credits/trust with their followers. Here are 10 things effective leaders do:

- Embrace Theory Y Assumptions: Effective leaders adopt a theory Y mindset. They trust and empower their team and believe individuals are naturally motivated to excel. This view of people sets the stage for a positive and productive leader-follower relationship.

- Leverage Referent Power: Effective leaders wield referent power. They lead by example, modeling the behavior and values they expect from their followers. They inspire loyalty and commitment by earning trust, respect, and admiration, which makes their influence enduring.

- Leverage Expert Power: Effective leaders recognize that knowledge is a powerful influencer. They continually enhance their own expertise and readily share it with their followers. Effective leaders provide guidance and mentorship based on a deep understanding of their field and leverage their knowledge to empower their followers to excel and grow.

- Use All The Power Bases as Needed: Effectiveleaders tend to use of the referent and expert power bases to influence their followers. That said, effective leaders understand and will use all the power bases depending on the follower’s needs, followership style, and the situation.

- Tailor Influence: Effective leaders tailor their influence strategies to align with each of their follower’s needs. Effective leaders ensure that each team member’s physiological, safety, belongingness, esteem, and self-actualization needs are met to foster a motivated and engaged workforce.

- Adapt to Followership Styles: Effective leaders recognize the diversity of followership styles within their followers. Effective leaders adapt their leadership approach to meet the unique needs and behaviors of each follower, ensuring that everyone can contribute effectively to the organization’s goals.

- Build and Maintain Idiosyncrasy Credits: Effective leaders continually invest in their trust bank by consistently meeting the group’s expectations, making sound decisions, and demonstrating unwavering integrity. By doing so, they accumulate idiosyncrasy credits that serve as a reserve of trust to draw upon when faced with challenging decisions or change initiatives.

- Foster a Positive Leadership Moment: Effective leaders understand that the leadership moment—the intersection of leader, follower, and situation—is where their influence is most potent. They create an environment where followers feel heard, valued, and empowered to contribute their best. In this atmosphere, leadership moments become opportunities for growth and innovation.

- Adapt to Changing Contexts: Leadership is not static; it evolves with changing circumstances. Effective leaders remain flexible and adjust their leadership approach/style to suit the context. Whether faced with a crisis, a new project, or a shift in team dynamics, they adapt while staying true to their core principles.

- Cultivate a Culture of Influence and Motivation: Effective leaders aim to cultivate a culture where influence and motivation are shared and propagated throughout the organization. Effective leaders inspire their followers to become leaders and create a culture of empowerment, innovation, and excellence.

The journey of mastering the art of influence and motivation in leadership is an ongoing one. Effective leaders understand that leadership is a science and an art. Effective leadership is about understanding the science and consistently applying it artfully, with authenticity and empathy. By embracing theory Y assumptions, using the power bases correctly, understanding individual needs, adapting to followership styles, and building trust through idiosyncrasy credits, leaders create lasting and meaningful impacts on their followers and organizations.